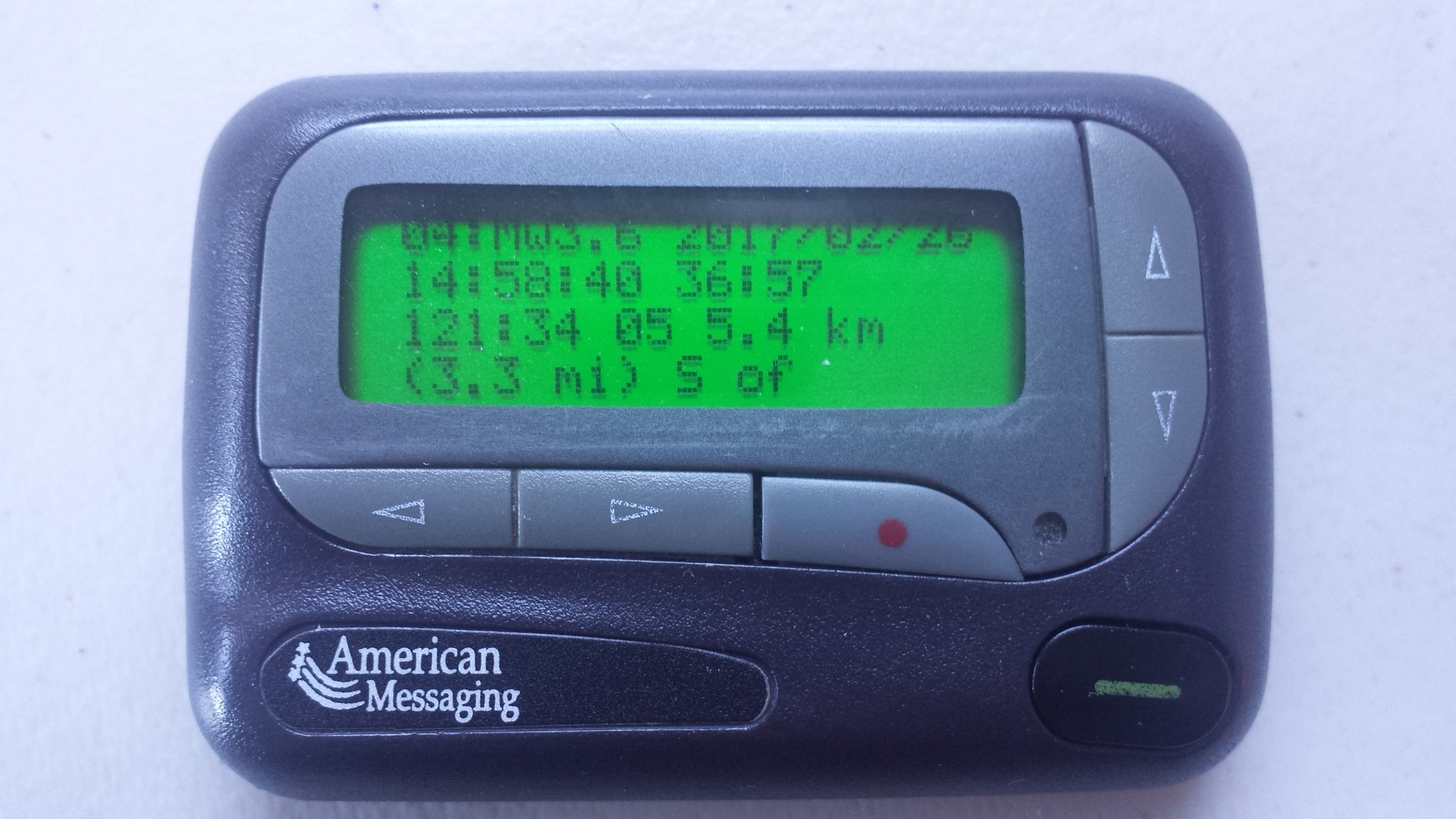

As a graduate student at the Berkeley Seismological Lab, doing pager duty is one of the things that accompany you throughout your PhD study. Why is it called pager duty? You carry a pager with you and wait for it to beep 24 hours a day for a week (the duty is rotating every semester). Whenever it beeps, you need to sit in front of a computer, and work out the mechanism of the earthquake. This is what a pager looks like:

Some of the young people don't even know what a paper is, and yes, we are still using them. It is amazing that there are still companies doing business with pagers. They have some advantages over the smartphone: the battery can last for months, they work in some places where no cell signal is available, and it is cool to show off to friends :-). Overall, it does the job nicely. Like I mentioned, whenever this thing beeps, I need to work on the earthquake it reports in the next half hour to one hour, even in the middle of the night. Luckily, during my PhD life, it only happend about 3 or 4 times that I needed to do this 1 or 3 am in the morning.

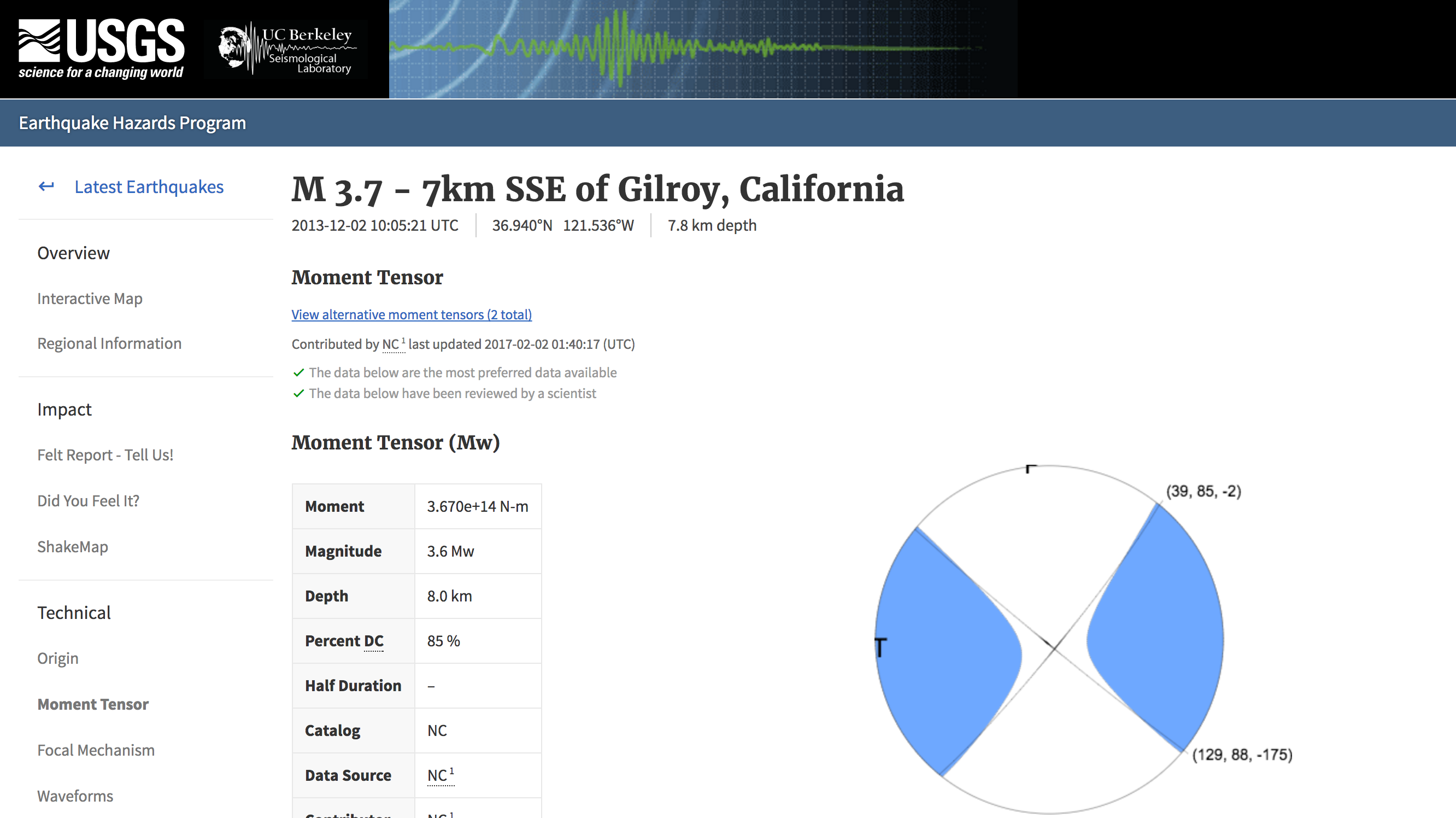

Ok, now you must be curious what we do after the pager beeps. Well, when it beeps, it means there was an earthquake larger than M3.5 in Northern California that just happened. Based on the waveforms recorded at seismic stations, a computer algorithm will generate a Moment Tensor Solution, which is a mathematical representation of the movement on a fault during an earthquake. This solution can tell us (mostly seismologists) how the fault actually moves. The alarm responders need to login to the system, review the result and do a better version of Moment Tensor Solutions. Once the result is reviewed, or a better solution is made, we will publish it to USGS. It will appear on the USGS website as the following figure

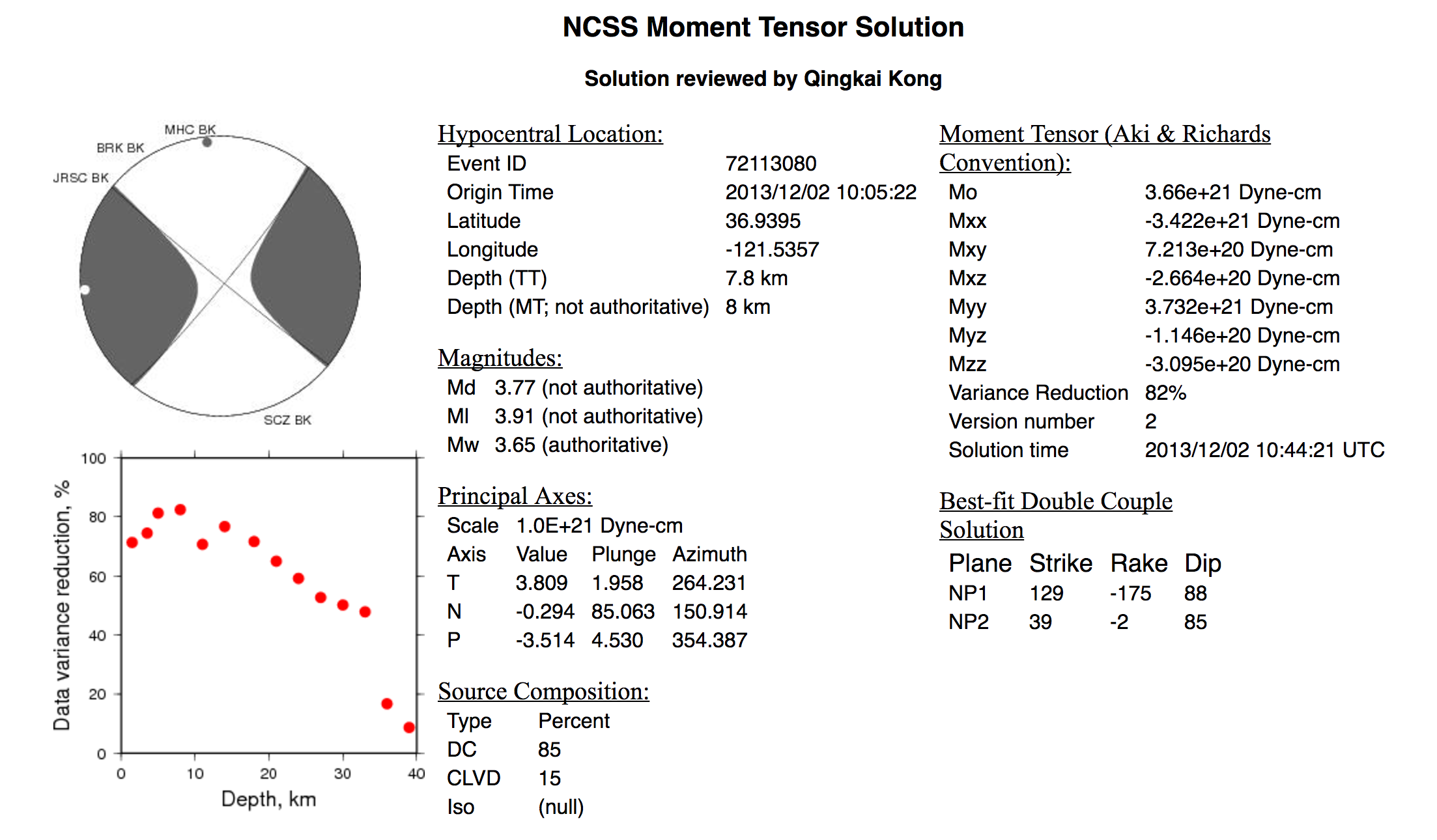

If you play around a little bit on the USGS website, and you can find more details about the solution the responder did, here's an example of one I did in 2013:

Don't worry if you can not understand what is shown here, it is designed for seismologists. And if you really want to know how it works, you can read this famous paper - A student's guide to and review of moment tensors. You can also check out the following video to get an idea of focal mechanism, which is a very close concept and you will learn how to read a beach ball diagram.

I think it is really cool that we students can contribute to the USGS earthquake website and leave our names there forever (I assume the USGS earthquake page will last forever, as long as we still have earthquakes).

Anyway, the pager duty is part of our graduate student life, and I believe that we will miss the feeling of doing duty in the middle of night after we graduate.

Fun facts

- The pager will beep two times a day for testing purposes, at noon and 3:30 pm. That's usually the time when we show off to friends or see the curious looks on other people's faces.

- During one tour of duty (7 days), responders will experience 0 or 1 earthquakes most of the time. Some lucky ones will have earthquake swarm occur during their duty :-)

- The average time to finish one earthquake moment tensor is about 1 hour.

- We switch duty on Wednesdays at 5 pm.

I downloaded the earthquakes larger than M3.4 in Northern California (I choose M3.4, because after we finish the moment tensor solution, the magnitude may change from M3.5 to a smaller magnitude, i.e. M3.4, M3.3, and so on) from 2011 to 2017, and made some quick figures to show some interesting facts.

Where do the earthquakes happen?

The red dots are the locations of earthquakes that our responders worked on in the last 6 years.

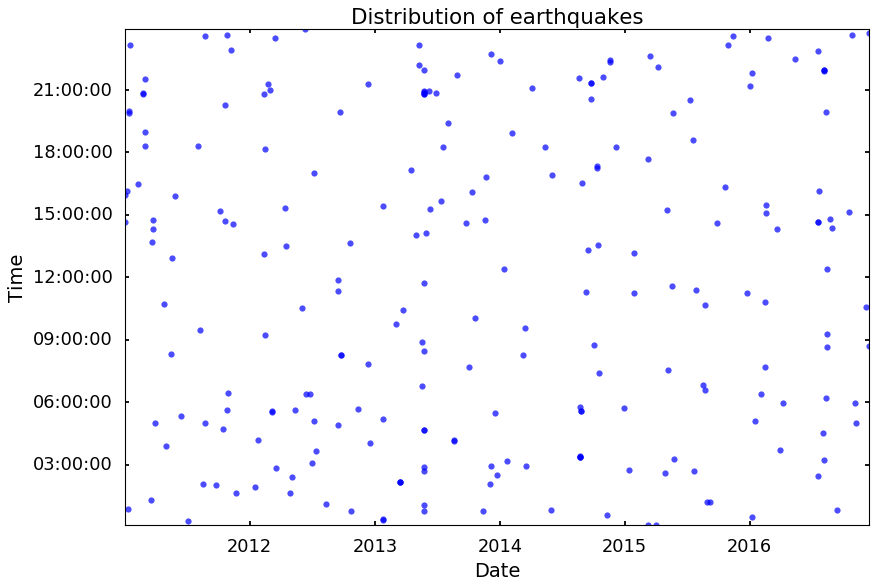

When do the earthquakes happen?

It seems earthquakes were randomly distributed.

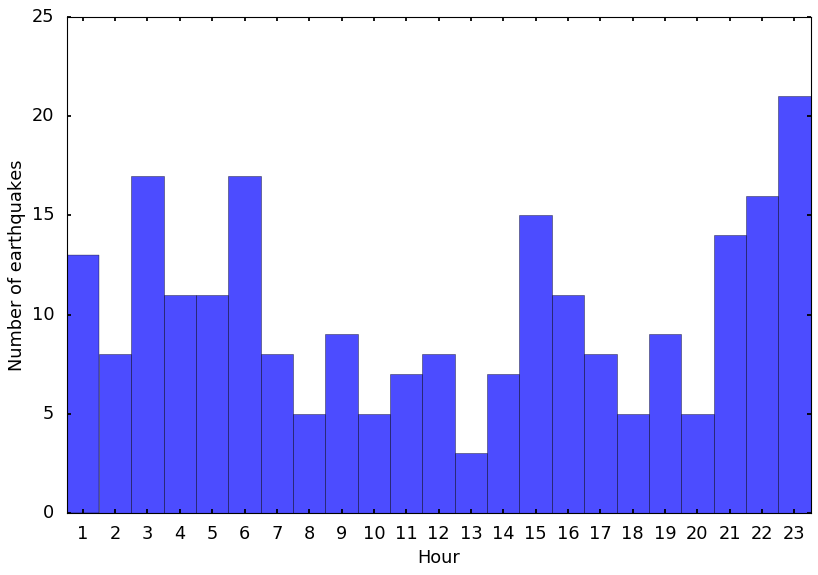

Which hour during the day do the earthquakes happen?

We have relatively more earthquakes in the middle of night in the last 6 years, how many of us remember the earthquakes that woke us up: hands up! I have at least have 3 or 4 cases in my memory. Also, in the last 6 years, relatively low number of earthquakes around noon, that is good, since everyone is at lunch :-)

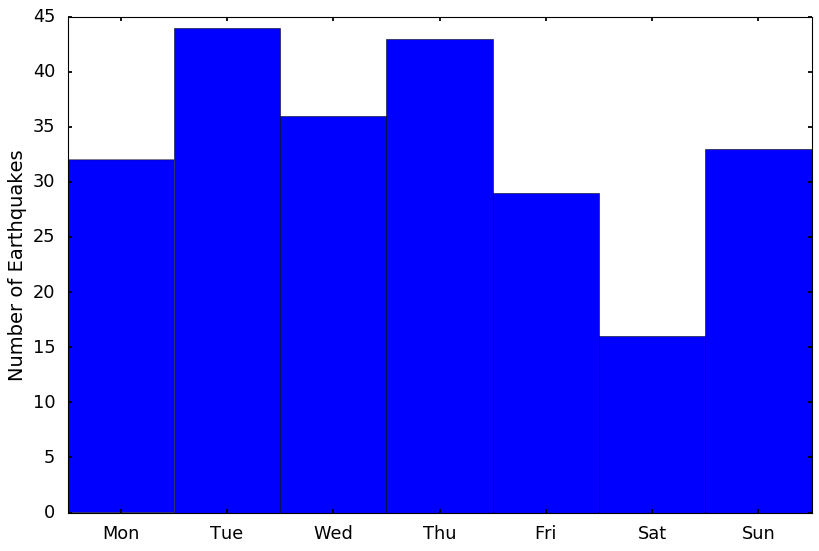

On which weekday do the most earthquakes happen?

Glad in the last 6 years that Sat and Sun are relatively low on earthquakes.

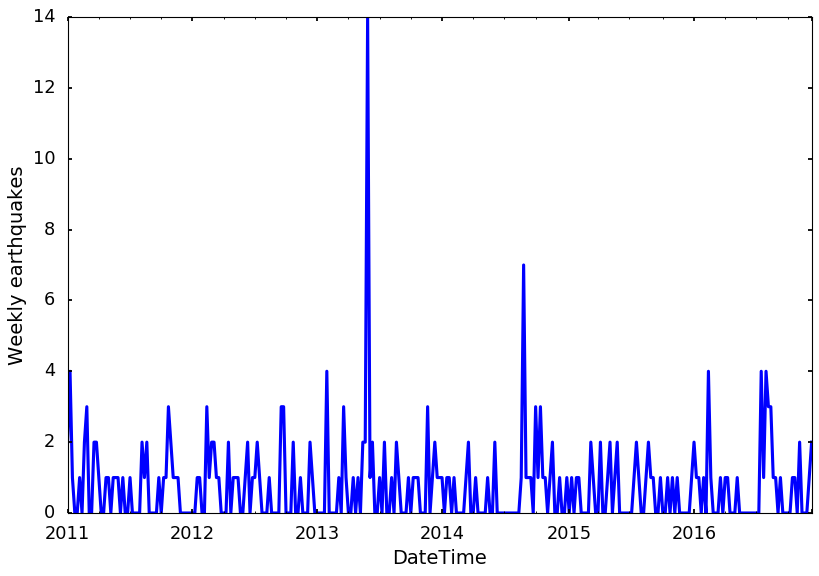

What is the number of earthquakes each week?

This figure shows the number of earthquakes in each week (Wednesday to next Wednesday), I am wondering who is the lucky one that had 14 earthquakes during the duty :-) Definitely not me.

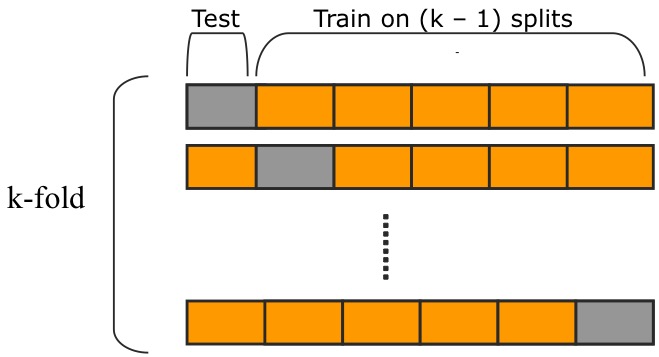

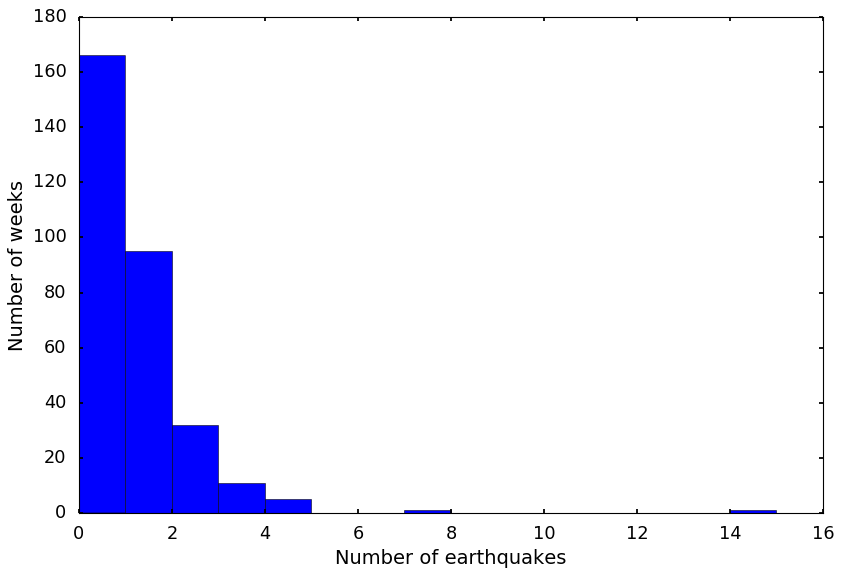

How many earthquakes do we usually see during duty?

This histogram shows us most responders did 1 or no earthquakes during the duty week (the first two bars show this, and more than half of the weeks in the last 6 years ended up with none earthquake). The following table is a quick statistic summary of the earthquake counts. The mean is 0.75 earthquakes per duty, and the 50th percentile is 0 earthquake, and 1 earthquakes for 75th percentile. So far today, I have already done two earthquakes (my lucky day!), maybe I will do more earthquakes this tour of duty and fall on the tails of the histogram.

| count | 311 |

| mean | 0.75 |

| std | 1.23 |

| 50% | 0 |

| 75% | 1 |

| max | 14 |

Why do we have an alarm response team? Why do we have to get up in the middle of the night to look at earthquakes?

This is copied from our Lab website!

As a seismological observatory, the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory has been involved in

earthquake informationfor over a century. Part of our mission is to monitor earthquake activity and to provide

timely and accurateinformation to state and federal agencies, to the media, and to the public.

Our primary responsibility is for local earthquakes. This has led to the development of the REDI project and the joint notification system with the USGS Menlo Park. Since much of this processing is automated, the Alarm Response workload has been significantly lightened. However, it is extremely important that the UCB alarm response people carefully review - and update, if necessary - information for larger events. This reviewing process must be done in collaboration with the USGS person on duty.

We also have a responsibility to respond to regional and teleseismic events. In this situation, our duties are to provide supporting information for the

authoritativeagency - for example, Caltech, the University of Washington, or NEIC. In general, we do not formally release our locations and magnitudes to the press if we have a solution from the authoritative group.

Conclusion

This blog was written because this might be my last duty since I will graduate soon and will be off duty. I even feel a little sad, the pager duty experience is somewhat fun while frustrating, and has been a big part of my life. I hope future students will enjoy the experience, and when I talk with them in the future, we will have so many things to cover.